[ This article is cross-posted from Khan Academy’s engineering blog. You can see the original here ]

The previous posts about The Great Khan Academy Python Refactor of 2017 and Also 2018 answered two questions: why and how did we refactor all of our Python code? In this post, I want to look closer at a major goal of this project: cleaning up dependencies between parts of our Python codebase.

Going into the project, we decided that we would build a dependency order into the structure of our Python code. Below, we’ll look at why dependency order matters, what our solution looked like, and how we went about implementing it.

Why is dependency order important?

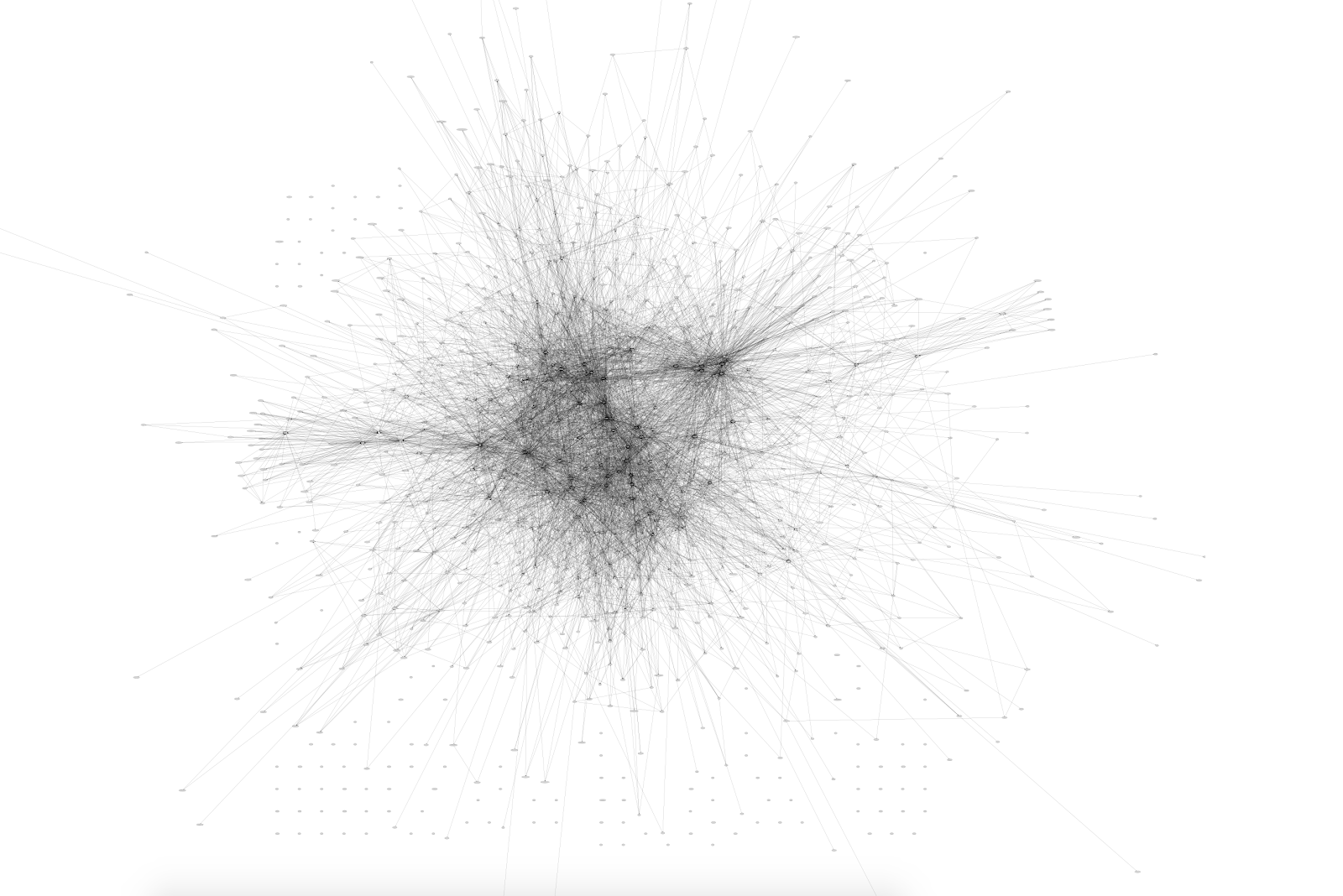

Take a look at a visual representation of Khan Academy’s code base:

Each dot in this image represents a module in our Python codebase. Each line represents an import of one module by another. tl;dr our Python code was a tangle!

Our dependency tangle looped back on itself in complicated and frustrating ways that posed a series of problems:

- Code didn’t live where it “should”, making it hard both for new developers to get oriented in the codebase and for experienced developers to find the particular functionality they’re looking for.

- Given an arbitrary change, we didn’t know what to test because we weren’t sure what code might indirectly use the code we changed.

- Intertwined dependencies made it difficult to draw boundaries between logically distinct parts of the codebase. This in turn made it harder to put stronger service-boundaries on our codebase.

In short, we had a lot of problems stemming from poor code organization.

In addition to these retroactive changes, our less-tangled codebase gives guidance to developers writing new code. Once we put in the work of defining what should and should not be depended on, we know to question any feature design that imports code from higher in the hierarchy. Since this dependency order is built directly into our code structure, we can automatically detect places in the codebase that are either poorly designed or poorly organized.

What does dependency order even mean?

In general, a dependency order is a set of rules deciding which files can be imported by a piece of code in a codebase. Some languages and frameworks implement dependency order by placing restrictions on possibly-problematic dependency practices. Since Python doesn’t provide any such rules, we decided to write some of our own.

We decided to create these rules by placing each Python file in our codebase into some conceptual bucket, which we call a “package”, and then defining an ordering on these buckets. The ordering rule is that a file in bucket X can import a file in bucket Y if and only if Y is lower than X in the ordering.

In other words, we divided all of our code into packages and placed these packages in a (mostly) linear order, where any given package is allowed to depend on packages lower than itself.

How we decided on the dependency ordering

It was not easy to decide how to order the packages. In theory any directed acyclic graph would be a legal ordering. But we decided to limit ourselves to a linear ordering, with one exception: we sometimes had several packages at the same “level”. These packages could not depend on one another, but any package above them could depend on any (or all!) of them.

We did this both to limit the universe of possible orderings, and to make it easier for humans to understand the final result. A linear ordering is easy to understand and explain to others.

However, this did open up an issue that we sometimes had to order two totally unrelated packages, and arbitrarily decide which one was higher and which was lower. Sometimes we would decide by calculating the number of bad dependencies both ways, and seeing which led to fewer bad dependencies!

How we untangled our codebase

In order to define and enforce our new dependency ordering, we decided to have our 40 packages be top level directories. Any time a file in a lower-level package depends on a file in a higher-level package, we can classify that as a “bad dependency”.

By defining what can (and more importantly, what can’t) be depended on by any given code feature, we can automatically detect places in our codebase that are architecturally problematic.

Once we had a set of packages and their ordering figured out, the first step towards implementation was to move each file in our codebase into the appropriate package, as described in the earlier blog posts. This allowed us to reason about our codebase’s dependency structure.

For example, consider the following excerpt from our package list and their descriptions:

lib/- Miscellaneous libraries. Utilities with some Khan-specific logic that are still general enough to be used across many components.

flags/- Infrastructure implementing A/B testing and feature flagging.

coaches/- Contains core models and mechanics for coach/student (including parent/child and teacher/pupil). Also includes code related to classrooms and schools.

These three packages above are listed in dependency order. In other words, it’s fine for the code in flags/ to depend on the more-general code in lib/. Similarly, the higher-level code in coaches/ implements the coach-student relationship, and should be able to use the lower-level infrastructure in flags/ to set up coach/student-related experiments.

Conversely, if a file in the flags/ directory were to import a file from the coaches/ directory, that would violate our dependency order and we would classify that as a “bad dependency”. Conceptually, this feels right; for example, it doesn’t seem like good design for the infrastructure implementing experiments to depend on specific, product-level experiments.

The second step in our process was to find the places where our code wasn’t following the new dependency rules. We used a script for this which output an HTML report on our dependencies.

Specifically, this was big list of all the dependencies in our codebase broken down by package. For example, here’s an excerpt from one of our package reports listing the bad dependencies (in red) and good dependencies (in green) for one file in the flags/ packages:

Flags:

- flags/experiments.py: depends on coaches/parents.py, coaches/students.py, coaches/teachers.py, sat/util.py, translations/videos.py, flags/bigbingo/bigbingo.py, flags/bingo_identity.py, flags/feature_flags/core.py, flags/gandalf/bridge.py, intl/request.py, web/request/ip_util.py, web/request/url_util.py

…

Diagnostic Report

Of 6787 total dependencies, there are 862 bad dependencies (12.700751%).

As you can see, the example given above was an actual issue in our codebase; the experiment infrastructure was depending on the product logic underlying specific experiments in the coaches/ package.

The third and final step was to fix hubs of bad dependencies. This process changed on a case-by-case basis — the cause underlying bad dependencies could be anything from poorly designed code to poorly defined packages.

More often than not, a file with lots of bad dependencies was indicative of bad code organization — either the file was in the wrong place, or the file was doing too many things. In these cases, we were able to use that code smell to refactor files relatively easily and improve our code organization.

For example, consider the following excerpt from flags/experiments.py, which has both a function used for logging opt-in experiments, and also a function used to determine if a user is in a classroom so that we can consider showing them coach-related experiments:

from __future__ import absolute_import

import coaches.students # BAD DEPENDENCY

import coaches.teachers # BAD DEPENDENCY

def log_opt_in_experiment_event(user_id, experiment_name,

event):

# ... add analytics for an event

def is_classroom_user(user_data):

"""Determine if user is shown classroom A/B tests"""

if coaches.teachers.classified_as_teacher(user_data):

return CLASSROOM_USER

if (user_data.classroom_user_status !=

UNKNOWN_CLASSROOM_STATUS):

return user_data.classroom_user_status

coaches.students.defer_classroom_status_update(

user_data, caller='is_classroom_user')

return user_data.NOT_CLASSROOM_USER

In this experiment, the bad dependencies are coming from the second function, and they indicate a valid organizational problem: is_classroom_user boils down to an implementation detail for coaching-specific experiments. Since, implementation of specific experiments is outside the scope of experiment infrastructure, flags/experiments.py is trying to do something outside the scope of its package.

Thankfully, this is a pretty easy fix: we can just use slicker to move the offending function to wherever the coach-related experiments actually live (in this case, coaches/experiments.py).

After moving this function, flags/experiments.py won’t depend on coaches.teachers or coaches.students, and our updated package report will look like this:

Flags:

- flags/experiments.py: depends on coaches/parents.py, sat/util.py, translations/videos.py, flags/bigbingo/bigbingo.py, flags/bingo_identity.py, flags/feature_flags/core.py, flags/gandalf/bridge.py, intl/request.py, web/request/ip_util.py, web/request/url_util.py

…

Diagnostic Report

Of 6787 total dependencies, there are 860 bad dependencies (12.67128%).

And just like that, our codebase is two bad dependencies cleaner. Of course, the fixes are rarely so small or straight-forward. We’d often find tangles of poor code structure that would decrease bad dependencies by quite a bit. The process was roughly the same though and can continue ad infinitum; given more time to work on the project, we’d simply iterate on steps two and three (looking for bad dependencies and then breaking them up) making the codebase incrementally cleaner.

The results

On one hand, we weren’t able to get rid of all of our bad dependencies – we still have a whitelist of about 750 imports that violate our new rules.

On the other hand, getting to a codebase that exactly matches our self-imposed dependency structure doesn’t prevent us from getting much of the benefit that such an architecture provides. Even with the many exceptions to our new dependency restrictions, it is much easier to reason about where functionality lives and how to test a given piece of code.

To start, one big win is that we were able to record a measurable improvement in our codebase’s structure! Having 1) built out a formalized notion of what a bad dependency is and 2) written tools for finding them in our codebase, we’ve been able to measure the “goodness” of our dependency structure over the course of the project.

When we first took this measurement, we found that about 15.2% of all of our inter-package dependencies were bad. Taking this measurement the codebase in production right after the end of the project, we had reduced the percent of bad dependencies to 7.8%.

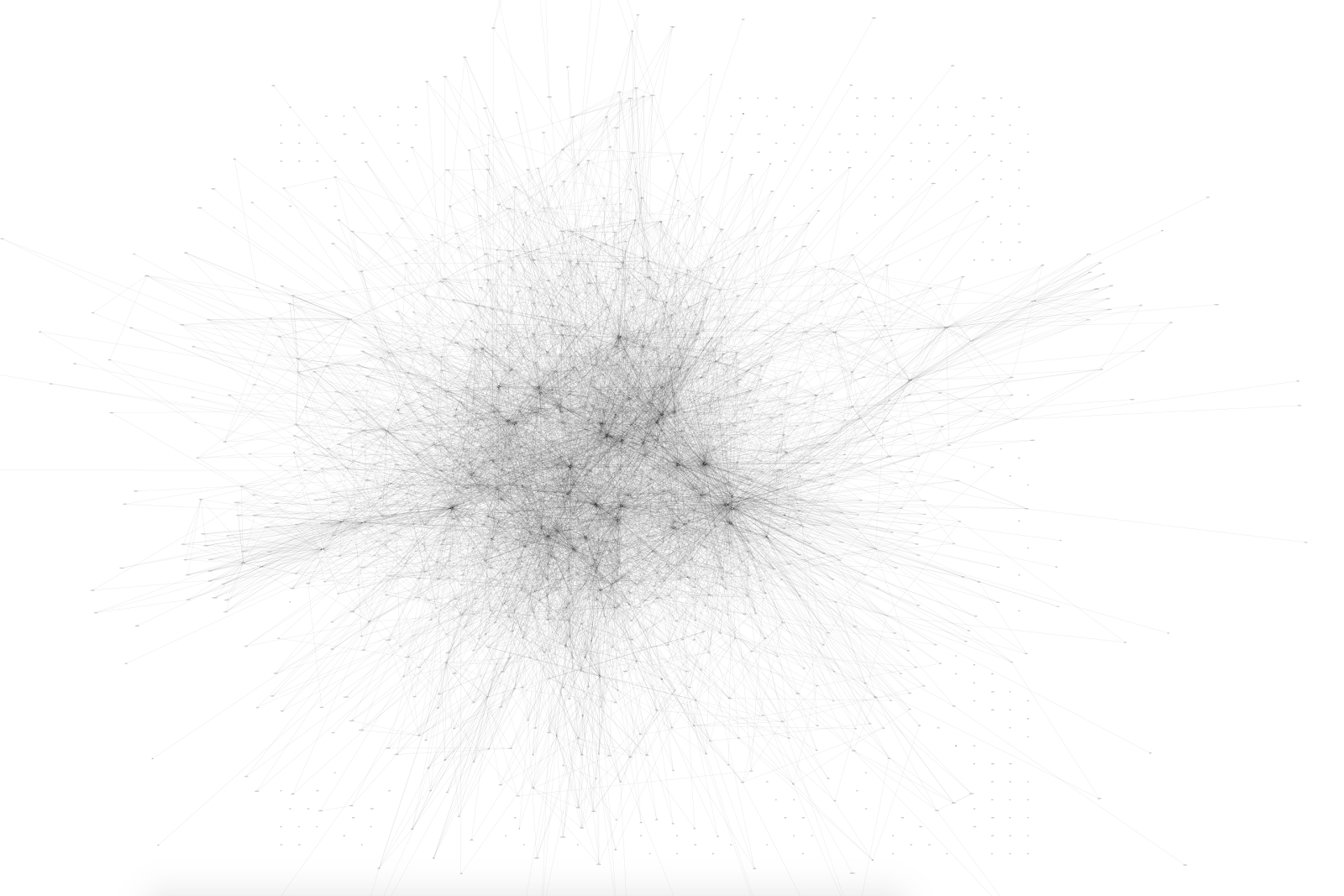

7.8% may still seem like a lot, but you can visually see the difference. Below is the dependency graph generated after our changes. Compared to the first tangle, we see that a lot of the dependencies that had been scattered all over the place have now been concentrated into a few clusters around our inter-package APIs, making the tangle appear… lighter.

What’s more, the benefits of this continue to help us develop clean code quickly. We now have a check that’s run at commit time that will let you know if your changes added a new bad import. In other words, you can’t accidentally introduce dependencies on higher-level code; if you’re going to violate the new rules, you have to do so explicitly.

These effects, in tandem with the clean-ups and refactors that came along with our dependency-chasing process above, left our codebase in a good place. Our self-imposed dependency order will help us develop faster and better in 2018 and beyond.

Big thanks to all of my teammates who helped get this blogpost from its draft to publish, especially Kevin Dangoor, Scott Grant, Ben Kraft, and Craig Silverstein.